Within the industry, the role of an agile coach is not consistent or clearly defined. It involves a mix of traditional coaching, mentoring, teaching, and consulting. Both Bill Gates (former CEO of Microsoft) and Eric Schmidt (former CEO of Google) have publicly stated that everyone needs a coach. Eric goes on to say that one challenge that everyone has is seeing themselves as others see them and that having a coach is critical to giving people perspective. This brief document is designed to lay out a high-level understanding of what is needed to get started and how we will work together. This list is not exhaustive and may be modified in a specific situation by mutual consent.

For coaching to work, the client and/or teams needs to answer yes to the following questions:

Does the client/team have clear goals that focus on delivering business value? – As a client, you need to have a clear goal of business values you would like to improve. Change for change’s sake doesn’t work. A coach can help you find clarify your goal, but the goal is to improve business value, not become agile.

Is the client/team committed to achieving your goal? – Do you have the right people in place? Part of committing to achieving your goal is to have the right people engaged and willing to participate. This will include representatives from business, technology, operations, etc… This might mean you need to have people several levels above you onboard and willing to actively engage in the process.

Is the client/team motivated to work with the Coach? – The client/team must have a burning desire to improve. They must have a sense of urgency to make improvements. Without a sense of urgency, any change will be minimal and short-lived.

Does the client/team have realistic expectations from the Coach? – The role of an agile coach is to guide and help the clients but the client needs to do the work. The work to make improvements cannot be dictated by or delegated to the coach or to anyone else.

Is the client/team ready to invest time, money and energy in the coaching process? – Making improvements is hard work. It takes more time, money and energy than originally planned. If the client/team is not allowed the time, money or energy to dedicate to improving business values, then it is better to not start.

As we work together, we agree to the following:

Everything is voluntary. – We know that you are capable of making your own decisions. We are not the Agile police. We will share observations and suggestions for improvement, but it is ultimately your responsibility to do the hard work of making changes to the organizational systems you work within.

We work together through mutual respect. – The client and the coach are experts in their domain. The client knows what is needed within their business line. The coach has experience on how to improve systems to deliver results. By respecting and combining this expertise, we will work together to find the best ideas for the organization.

Positive Intent. – As we seek to understand the current situation, what’s working and possible areas for improvements for the system, we will question why things are the way they are. Hindsight is always 20/20. At all times, we will assume that the people did the best they could with the knowledge, understanding, and time limitation presented to them.

We are looking at the system as a whole. – The design of the system accounts for the majority of the performance within a group, a team, or a department. We agree to look at the system as a whole to determine how the organizational systems either contributed to or inhibited from, providing value for the customer.

Leadership is responsible for defining and improving the system. – People are the ones that build and designed the systems used within an organization. These systems were built over time to address specific issues that may or may not currently exist within the organization. In many cases, leadership is the only one that has sufficient influence to make changes to the system. Since system design accounts for the majority of the performance, leadership’s biggest wins come from improvements to the system.

Change needs to be modeled and demonstrated by leadership. – Whether we like it or not, leaders are always leading by example. A leader’s actions communicate far more than the words they use. We agree to share observations and suggestions with each other on ways to model and demonstrate the needed change within the organization.

The coach will ask difficult, uncomfortable questions. – The role of a coach is to help the client and organization grow by creating awareness through transformational questions. These questions will dig into areas that are uncomfortable and challenging. At times, the questions will seem not to be relevant to the immediate situation. The primary goal of transformation questions is to create awareness of possibilities. Only by looking at things differently, can we find new solutions and create lasting change.

Agile coaching is about mindset more than a toolset. – Albert Einstein is credited with the idea that “We can’t solve problems by using the same kind of thinking we used when we created them.” Agile at its core is a mindset, not a toolset. We can decide to implement and use different toolsets, but the toolset will always adapt to the mindset. Real, lasting change can only happen when we change how we think. This change in thinking will support our change in action.

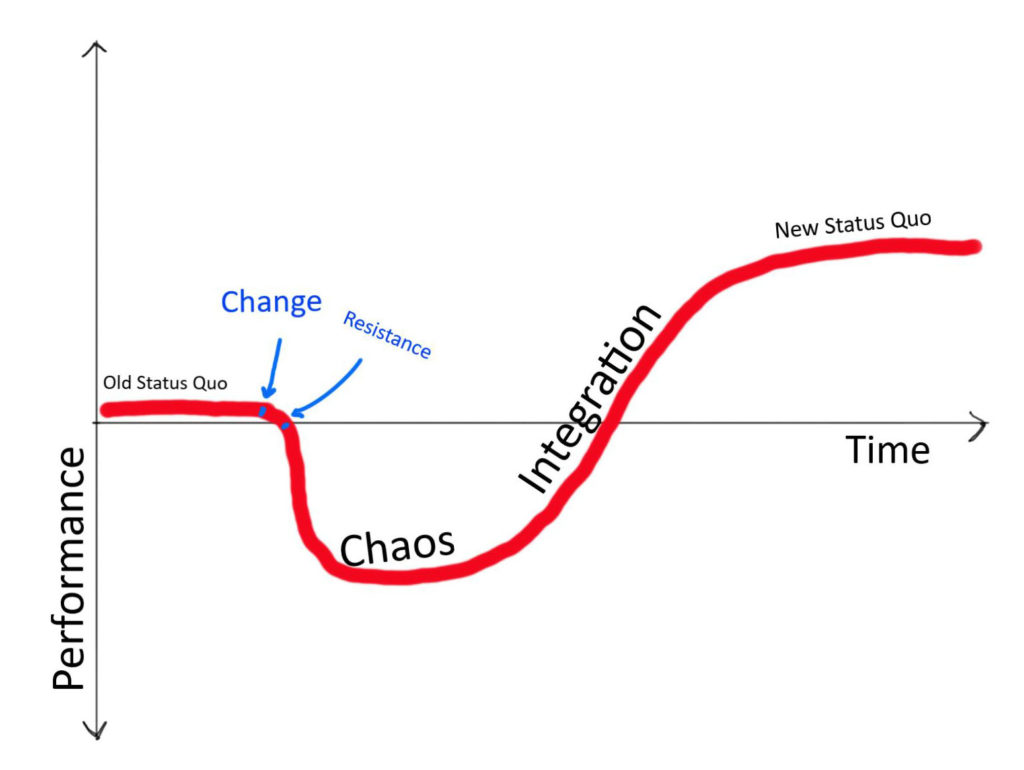

Growth only occurs outside the comfort zone. – It has been said that there is no growth in the comfort zone, no comfort in the growth zone. Humans are creatures of habit and resist change. As a coach, we will support you in your growth zone. As a client, we ask that you are willing to push the boundaries of your comfort zone. The more you do, the bigger your comfort zone becomes.

We can not change others, only ourselves. – The only person we can really change is ourselves. By pushing others to change, we create resistance and damage relationships. Change should be done by invitation only. Change is a voluntary action, motivated by an eagerness to learn.

Featured Image by Cytonn Photography on Unsplash